History of the Phrygians

According to Akurgal, the Phrygians were "one of the Balkan tribes that came to Anatolia around 1190 BC. However, they emerged as a political community after 750 BC. [...] Despite their Indo-European origins, they quickly became Anatolianized, and although they remained under Hellenistic and Late Hittite influences, they developed a unique and Anatolian culture."

According to Umara, "The Phrygians were, according to many evidences, a people related to the Thracian hordes that destroyed the Hittite Empire."

While this is the general view about the Phrygians, their origins are debatable. However, the view we accept is that the Phrygians were of Thracian origin.

The Thracian tribes gave their name to today's Thrace. The origins of these people are also controversial.

According to Erzen, it appears that the country was inhabited by a native population, albeit much less frequently, long before the people known historically as Thracians arrived in the country through migration. We have little information about the racial makeup of the earliest inhabitants. Furthermore, our knowledge of the intermingling of the ancient native population with the migrant Thracians is scanty and inadequate. According to the documents that have survived to us, the Thracians were quite strongly representative of the Northern European racial type until the late antique period.

The Thracians also have linguistic ties to Northern Europe. The Thracian and Phrygian languages belong to the Satem group of the Indo-European language family.

Although it is not yet certain, it is thought that the Phrygians were related to the Celts and shared a common esoteric heritage.

During the years when the Hittite Empire was collapsing, Anatolia began to be influenced by migrants arriving from the northeast via the Caucasus and from the west via the Straits. Those arriving from the east were called Mushki and settled in the Elazığ region. Those arriving from the west were called Brig. Gradually migrating into Central Anatolia, the Phrygians, one of these tribes, reached the Polatlı region, or rather, their capital, Gordion. After a long period of darkness, the Phrygians, who became a centralized kingdom in the eighth century BC, are thought to have formed from the fusion of these tribes.

Among them, the Mushki have appeared in Assyrian documents since the twelfth century BC. The name Mita, thought to be the source of the legendary Midas, has even been encountered in Hittite documents.

A point worth noting here is the time elapsed between the initial raids and the establishment of the Phrygian Kingdom. As the Hittite Empire collapsed, the Mushki people were the first to establish a presence in Anatolia. However, the Phrygian state took much longer to emerge.

Sedat Alp explains this as follows: The Assyrians were aware of Mita, the king of the Mu'ki country. It has long been accepted that this was the Phrygian king Midas. While this equation might initially suggest that Phrygia and the Mu'ki country, known only from Assyrian sources, were the same country, considering that, as Ekrem Akurgal first demonstrated, no Phrygian material remains were found in Anatolia before the 8th century BC, and that the Mu'ki country was present in the upper Tigris region as early as the time of Tiglathpileser I (approximately 1112-1074 BC), it is difficult to accept that the Phrygians and the Mu'ki were the same people. At best, the Assyrians might have simply attributed this. It is noteworthy that the Assyrians do not mention the Phrygians. Perhaps the Phrygians' political influence over the Mu'ki people led to their association with the Mu'ki people.

This uncertainty is undoubtedly due to the Dark Ages that Anatolia experienced after the invasions that destroyed the Hittite Empire. The primary reason we call this period the "Dark Ages" is the lack of sufficient documentation. Another reason is the failure to establish political unity. Political unity in Anatolia was established only in the eighth century BC.

Assyrian records from this period also contain references to the Phrygians. An inscription by Sargon II from 709 BC includes the phrase "Mita, who did not bow to the kings before me."

After the peace treaty with the Assyrians, the name of the Mushki king Mita disappears from Assyrian records, but the Phrygian king Midas begins to appear in Greek sources. In other words, relations between the Phrygians and the Greeks began from the seventh century BC onward.

As we have stated before, Greek sources may not be sufficient due to their limited historical information, but since they are the most important and detailed sources at the moment, we have to base some of our information about the Phrygians on them.

Greek sources state that the first king of the Phrygians was Gordios, and that the Phrygian capital, Gordion, took its name from this king. It's highly likely that the name of this city, whose ruins are located near Polatlı today, originates from earlier Anatolian languages and was later coined by the Hellenes. In fact, there's no other significant source for Gordios other than the account of the Greek Arrianos.

The legendary king of the Phrygians was Midas. It is unclear whether Midas was the name of a single person or a name given to rulers, but the fact that the name Mita appears in both Assyrian and Hittite sources confirms that at least one person ruled with this name.

As we've mentioned before, the name Midas is implicated in many legends. These legends may be ancient Greek legends, but they may also be of Anatolian origin.

There's no doubt that Phrygia was a truly great power in the region during this period. Although the legend of Midas turning everything he touched into gold is an esoteric motif, it originated in accounts of Phrygian wealth during this period. Midas' dedication of his throne to the temple at Delphi also astonished the Greeks who saw it at Phrygia's wealth.

Relations between the Greek peoples and Phrygia also intensified during this period. The Greeks' view of Phrygia as the oldest people stems from the fact that the Greek peoples first encountered Anatolian culture through the Phrygians during this period.

However, these bright days of the Phrygians did not last long and the Phrygian State became history under the Cimmerian invasions.

However, the Phrygians and Phrygian culture survived in Anatolia until the Roman period, and ancient beliefs survived in this region called Phrygia.

We can say that the Phrygians are one of the most interesting Anatolian civilizations and the one that influenced the Greek civilization the most.

The Phrygians lived in the region between Eskişehir, Kütahya, and Afyonkarahisar in Anatolia. The Phrygians, who encountered Greek communities in these regions, were seen by the Greeks as the indigenous people of this region.

In fact, Greek civilization attributed every interaction it received from Anatolia to the Phrygians, because, according to the Greeks, the Phrygians were the oldest people. Herodotus describes this as follows:

"The Egyptians, before the time of Psammetichus, considered themselves the first people in the world. But when the day came when Psammetichus took over the kingdom and became curious about who the first people were, I say from that day on, although they still considered themselves the oldest of all, they came to the conclusion that the Phrygians were even older than themselves. When Psammetichus, despite his inquiries, could not find out who the first people were, he resorted to the following solution: He gave two newborn babies at random to a shepherd, and they were to be put in a pen and raised in this way. The shepherd would take the goats to them at a certain time, give them milk and a good meal, and then go about their own business. The reason Psammetichus did this was to catch the first word that would come out of the children's mouth after they had outgrown their squealing. And indeed, that was what happened. Two years later, one day, the shepherd opened the door and went in. The two children who were sitting on their knees in front of him, extended their hands and shouted "Bekos." The shepherd said this first When he heard it, he said nothing, but when he heard the same thing on each subsequent visit, he informed his master and, at his request, took the children to him so that he could see for himself. After hearing it with his own ears, Psammetichus began to search for people who had called anything bekos. By searching for information, he learned that the Phrygians called bread bekos. Thus, and holding on to this clue, the Egyptians admitted that the Phrygians were older than themselves. (II,2)

In fact, in esoteric stories from ancient Greece, the hero is the legendary Phrygian king Midas, to indicate that they take place in ancient times. Thus, the Midas stories spread by word of mouth like ancient fairy tales.

Phrygian culture continued to survive within Greek and Roman civilizations.

The region where the Phrygians lived was referred to as Phrygia in Roman sources until the fifth century AD.

Phrygian Language

Phrygian spread from Central Anatolia to Kütahya and north to Kastamonu. Phrygian is linguistically similar to the language of the Macedonians' ancestors. While it shares similarities with Greek, it is not as similar as the language of the Macedonians' ancestors. There is no consensus yet on the origin of this language. While some argue for Indo-European origins, others claim it was an indigenous language. Phrygian did not vanish with the fall of the Empire and remained in use in the mountainous regions until Roman times. The Phrygian script, found in many places in Anatolia, has not yet been fully deciphered.

Phrygian Beliefs

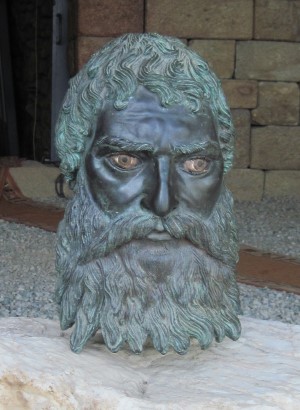

The most well-known of Phrygian beliefs is undoubtedly the cult of the mother goddess. The Phrygian mother goddess, called Kybele by the Greeks, was actually Kubaba, one of Anatolia's oldest goddesses.

When the Phrygians came to Anatolia, they undoubtedly came into contact with the local tribes during the Dark Ages and adopted this cult.

Many Kybele sculptures in the Anatolian Civilizations Museum today give an idea about the prevalence of this cult.

Phrygian mother goddess figures display a tower-shaped crown on her head. This is interpreted as a symbol of her sovereignty.

Another name for the mother goddess, also called Kubile by the Phrygians, is Agdistis.

One of the most important places of worship of the goddess was Pessinus, located in what is now Sivrihisar. It was here that the goddess's idol, most likely a meteorite, descended from the sky, was found. This site, which was the center of mother goddess worship for many years, retained its importance even during the Roman period. To win the war against Carthage, the Romans took this stone to Rome in 204 BC and named it Magna Mater (Great Mother). Strabo (64 BC - 21 BC) describes this place and its cult as follows: "Pessinos was the largest commercial center in that part of the world, and here stands the temple of the highly revered Mother of the Gods. It is called Agdistis. In ancient times, priests were also rulers and reaped the benefits of the priesthood. However, although the commercial center still stands today, the priests' authority has been greatly diminished. The sacred precinct was rebuilt by the Attalids, as befits a sacred site, with the addition of a temple and white marble porticoes." In response to Cybele's prophecy, the Romans attempted to seize the goddess's statue, thus making the temple famous. Just as Cybele took its name from Mount Kybeon, the land of Dindimen�ª took its name from Mount Dindymon, which lies above it. The Sangarios River flows nearby, and on this river are found the remains of settlements belonging to ancient Phrygians, Midas, and even Gordias, who lived before his time, and others. However, these traces are not cities, but rather rather large villages. Strabo, of course, described the site from the perspective of his time. However, later excavations also unearthed the temple of Cybele and Roman ruins.

Pessinus was the scene of ceremonies held in honor of the mother goddess and served as a center for those who dedicated themselves to her. Men also cut off their penises here to dedicate themselves to the mother goddess.

Attis cult ceremonies were also held here. Since Anatolia's mother goddess was also mother earth, a god was needed to fertilize her. Attis was the god who fertilized Cybele. However, this god died at the end of summer, and thus nature lay dormant until the god's rebirth in spring. This motif, also seen in Mesopotamian beliefs, coexisted with the cult of Cybele and entered Greek mythology in the form of Adonis. This cult also gave rise to some mystery cults. These cults continued in Anatolia after the collapse of the Phrygian state.

Barnett points out a very interesting aspect of the Attis legend:

“According to one version, Agdistis was an androgynous monster who fell in love with the handsome Attis, son-in-law of the king of Pessinus, and led him and his city to destruction, castrating herself and thus becoming female.” A much-abbreviated, milder version of the story tells of Agdistis’s love for Attis, who was killed during a boar hunt in the prime of his youth and beauty. But each year in the spring, through the practice of an enthusiastic mourning ritual involving self-mutilation, Attis was resurrected, thus reviving the dead forces of nature. During the ritual, the excitement reached such a high point that the goddess’s most ardent devotees castrated themselves in honor of the goddess and Attis. This wild worship of the goddess—for whom her handsome lover suffered and died—early filtered westward into Ionia, but was reflected, in a softer and indeed more romantic form, in various Hellenic myths connected with Anatolia. This In myths, the theme of a young man who falls in love with a goddess but whose love brings her misfortune emerges. Sacred places to Cybele, or the mother goddess, were believed to be in mountains or rock formations. Numerous altars built for this purpose have been found in Anatolia. Furthermore, niches containing a statue of Cybele are also found on these altars and in the rocks.

The most important of these are undoubtedly the altars around Midas City (Yazılıkaya). The rock-cut altars here, and especially the throne-like carvings accessed by steps, indicate that these were cult centers. The famous Midas Monument was also a significant site of the mother goddess cult, as evidenced by the inscription "MATEP" (mother) inside.

Altars of this type are also found elsewhere in Anatolia. Some of them also bear Phrygian inscriptions.

Besides the worship of the Mother Goddess, the Phrygians also worshipped the Sun god Sabazios and the Moon god Men. Of these, Men can be considered particularly related to the Moon god of ancient Anatolia. The fact that this god is depicted with a crescent moon on his shoulder further supports this view. It's also possible that these deities were later adopted by the Phrygians.

Beyond these, it's possible to find traces of ancient Anatolian beliefs among the Phrygians. Animal motifs found in ancient Anatolian beliefs are also found among the Phrygians. Plaque plaques depicting a bull and lion fight, unearthed in the Pazarlı excavations, are also very significant in this regard.

Burial Customs of the Phrygians

There were two main burial customs among the Phrygians. This type of burial, thought to be practiced for the nobility and the wealthy, appears to have been practiced in Phrygia for a long time. It is thought that the poor were buried or cremated. However, since a sufficient number of graves belonging to the poor have not yet been found, it is too early to say anything about this.

One of the burial customs was burying the dead in rock-cut tombs. Numerous rock-cut tombs dating from the Phrygian period have been found near the city of Midas and throughout much of Phrygian territory. Unfortunately, these rock-cut tombs, some of which were monumental tombs, have been severely damaged by treasure hunters (and even Romans, if we include them) over the centuries.

The most well-known Phrygian burial custom was tumuli, or mound-shaped tombs. The tumulus tradition, common in Gordion and Ankara, as well as in other Phrygian cities, is thought to have come to the Phrygians from Thrace. Tumuli, constructed by piling earth over a wooden burial chamber, were constructed in various ways.

Sevin writes about tumuli:

The wooden construction of the burial chambers in Phrygian tumuli is the result of an advanced technique. The dead were initially laid out on wooden couches without being cremated, and from the late 7th century BC, cremation began, most likely due to influences from the west, via Greece. After the bodies and grave goods were deposited in the wooden burial chamber and the wooden roof was closed, the chamber was covered with a large mound of earth. Certain rules had to be followed in the construction of the mound, otherwise it would have been impossible to prevent the pressure exerted by the thousands of tons of earth on the wooden burial chamber. Once the roof of the burial chamber was built and stones and earth were piled on top, it was impossible to open it again. However, the only danger was grave robbers. Therefore, careful location selection was necessary. The burial chambers, located beneath the mound of earth, were located in the center of large tumuli, directly below the summit. In lower tumuli, concealment of the burial chamber was essential, and therefore the burial chambers were placed in remote locations. The most famous tumulus is undoubtedly the Midas Tumulus, also known as the Great Tumulus. Excavations there have unearthed bronze funerary artifacts, wooden artifacts, and numerous archaeological artifacts.